The amount of systematic error is inversely related to the validity of a measurement instrument. Here are two everyday examples of systematic error: 1) Imagine that your bathroom scale always registers your weight as five pounds lighter that it actually is and 2) The thermostat in your home says that the room temperature is 72º, when it is actually 75º. Systematic Errors: Systematic or Non-Random Errors are a constant or systematic bias in measurement.

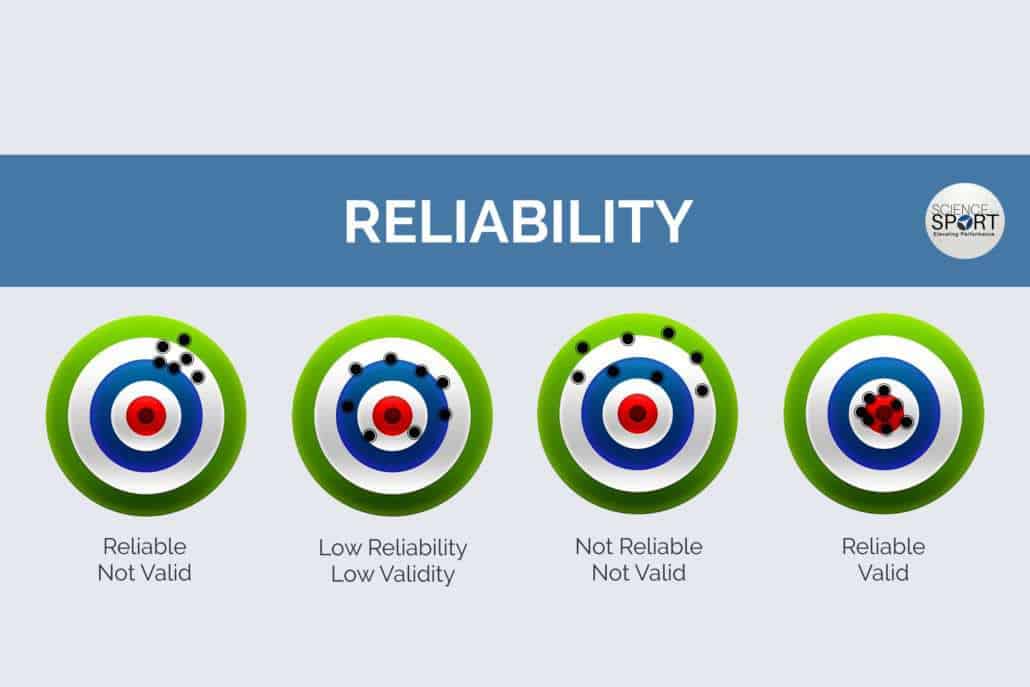

As the number of random errors decreases, reliability rises and vice versa. The amount of random errors is inversely related to the reliability of a measurement instrument. Random errors include sampling errors, unpredictable fluctuations in the measurement apparatus, or a change in a respondents mood, which may cause a person to offer an answer to a question that might differ from the one he or she would normally provide. They are inherently unpredictable and transitory. Random errors in measurement are inconsistent errors that happen by chance. Random Errors: Random error is a term used to describe all chance or random factors than confound-undermine-the measurement of any phenomena. Target C shows a measure with good validity and good reliability because all of the shots are concentrated at the center of the target. Target A shows a measurement that has good reliability, but has poor validity as the shots are consistent, but they are off the center of the target. The shots are neither consistent nor accurate. In the illustration below, Target B represents measurement with poor validity and poor reliability. Reliability and validity are often compared to a marksman's target. Validity is the degree to which the researcher actually measures what he or she is trying to measure.

Reliability means that the results obtained are consistent. Accurate results are both reliable and valid. All researchers strive to deliver accurate results.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)